In 2024, Moonstone Arts Center hosted almost 100 events with nearly 200 poets, both local and international. 75 of those featured poets contributed to this anthology.

"F.X. Baird is a... thoughtful and engaged writer, he offers perspectives on life, religion, and where to find optimism in what can be a difficult and alienating existence. "— Abby J. Porter, Mad Poet's Society

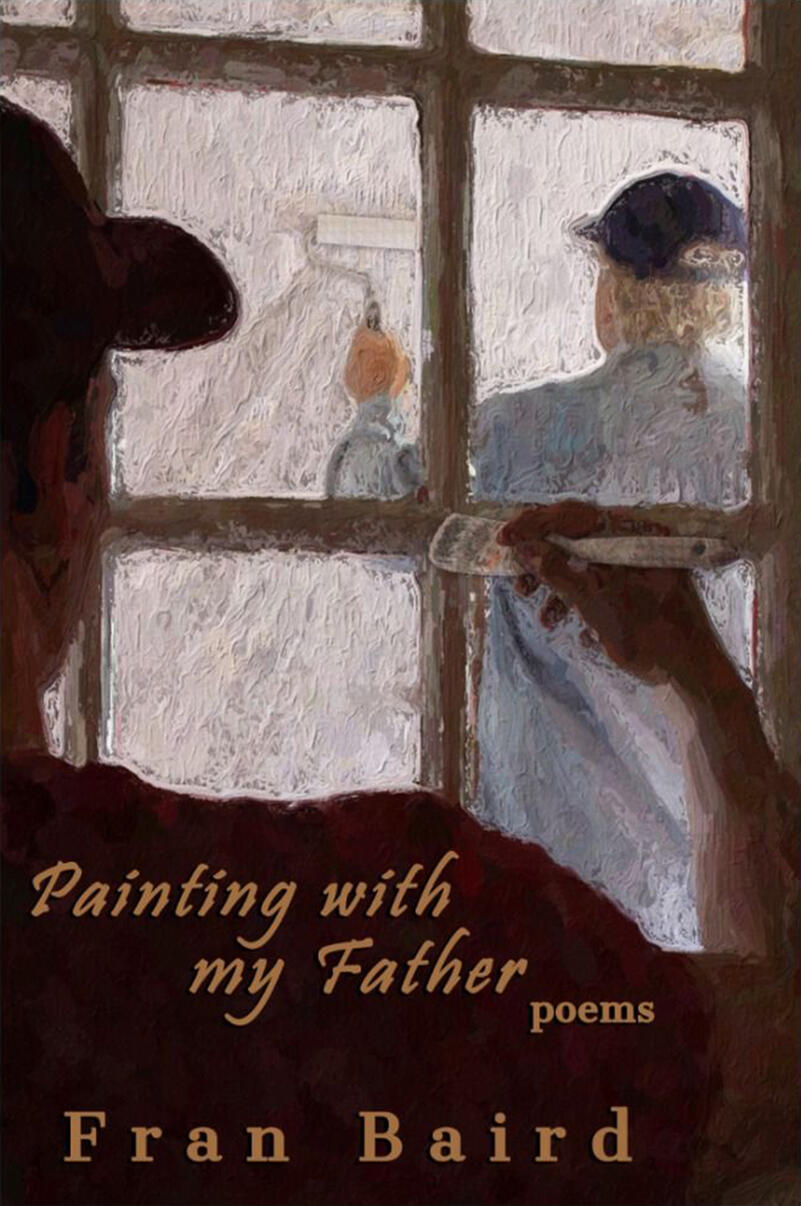

"In this radiant collection of poems, Fran Baird casts light on memory and the present moment, on family and the natural world, with keen observation and brave reflection."— John Philip Drury, author of Sea Level Rising

Neshaminy

I see no detail on the crow

I’m sure he sees my eyes

That only see his dark silhouette against a blaze of blue

A painter’s brush undipped in pastels

Sun and clouds have smeared behind him.Caw-caw, he breaks his shadow pose

Caw-cawing stiffly twice

He beckons to another to join him on his silver perch

A lamp planted in the black meadow

Here in this steaming parking lot.One faces east the other west

Searching their bleak domain

Hungry for dead things, while the thieving gulls from the sea hover

Far above, steal the higher vision

For meager meals that wait below.In my black coat, in my black car

I wait beneath a pole

The fake totem of Neshaminy Mall, plastic mock of myth

The crow’s orange cartoon beak hanging

Over the face of Eagle, Bear.Neshaminy Neshaminy

My voice still drums the name

I sing the ancient name and beat the drum of Neshaminy

Call the spirit of the hill to rise

Above the mantel of its grave.On the black skin that coats the hill

And silences the drum

I wait for Crow – Tell me where the spirit of the hill has fled –

I study Crow’s flight like a shaman

Searching the sky, reading his runes.Crows begin their dark ritual

Pierce the air with their beaks

Caw-cawing stiffly twice, twice again, they chant the ancient name

In their tongue, “Neshaminy, Caw-Caw,

Where, where have the fish people gone?”Creek flows I do not hear her voice

Fish swim and are not trapped

By Lenni Lenape. Do they come along the tidal marsh

Still salted by the green Atlantic,

Her gift, one hundred miles away?Over the land, over the creek

The cloud of Europe spread

Its Anglo names: Eddington, Logan, Gibbs; while the Lenape

Receded into Pennsylvania

And fled along the veil of tears.Their blood runs thin in names they left

Behind – no drums, no fish

Just Neshaminy. While on this hill mortician crows complain

Of the human tide that swept over

And covered the land with their flood.

Fran Baird

Copyright © 2009

Originally published in the Schuylkill Valley Journal, Volume 28, Spring 2009

Nominated for Pushcart Prize

Essays

Where we go to drinkPublished Schuylkill Valley Journal, Volume 30, Spring 2010

Excerpt:Baird’s poem “Neshaminy” was first published in the Spring 2009 Edition of SVJ and later appeared in the June 2009 issue of the Lenape Nation Newsletter. “Neshaminy” was nominated for a 2009 Pushcart Prize.

The clans of the Lenni Lenape Nation are the Native Americans who inhabited the lands that stretched from the Hudson Valley to the Delaware Bay when European settlers came to these areas of the eastern shores of the “New World” in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By “Nation” is meant a language group, and the Lenni Lenape were part of the Algonquin language group. Within the Algonquin-speaking group of nations, the Lenni Lenape were revered as the elders, literally “grandfathers,” and were often consulted as peacemakers to settle disputes between “tribes” or nations. Indeed, the word Lenape means “man” (as in mankind) or “the people,” and Lenni is the Lenape word meaning “original” as well as “genuine,” “pure,” “real,” and “true.” And so, they saw themselves as the true people, and the other Algonquin groups considered them the elders, the original people, and sought their counsel as such.…And there is the unique waterway, Neshaminy Creek, so named because of its two (nesha or nisa) bends where the Lenni Lenape trapped fish. The Neshaminy is a tidal estuary that sits at sea level and so the creek rises and falls with the tides of the Atlantic Ocean over one hundred miles to the east. The Lenni Lenape used this natural phenomenon by placing low wooden gates in the creek. At high tide, fish would swim over the gate and when the tide went back out would be trapped behind in the shallow waters, making it easier to spear them.

Music

“Queens of the Nile” performed by Little Stranger written by John Shields & Fran Baird

Where we go to drink

By Fran Baird

The clans of the Lenni Lenape Nation are the Native Americans who inhabited the lands that stretched from the Hudson Valley to the Delaware Bay when European settlers came to these areas of the eastern shores of the “New World” in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By “Nation” is meant a language group, and the Lenni Lenape were part of the Algonquin language group. Within the Algonquin-speaking group of nations, the Lenni Lenape were revered as the elders, literally “grandfathers,” and were often consulted as peacemakers to settle disputes between “tribes” or nations. Indeed, the word Lenape means “man” (as in mankind) or “the people,” and Lenni is the Lenape word meaning “original” as well as “genuine,” “pure,” “real,” and “true.” And so, they saw themselves as the true people, and the other Algonquin groups considered them the elders, the original people, and sought their counsel as such.As was the case throughout the North, South, and Central American continent lands, the Lenni Lenape’s encounters with the European settlers proved to be disastrous. Disease and war wiped out many and the nation, who were misnamed by the settlers “Delaware Indians,” and many were driven west, some settling near Pittsburgh, others migrating to Ohio and Oklahoma. Much later in the mid-nineteenth century, the “Delaware Lenape” purchased land from the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma and settled there. The Lenni Lenape that remained in the Eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey regions were never recognized as “tribes” by the U.S. Government and, over the course of many centuries, they “disappeared” into the landscape that was their home, where they once roamed freely, hunting, fishing, and farming.While the people seemed to disappear, their presence remained alive through their language, the Unami dialect in the southern regions (the Delaware Valley, Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and the Delaware Bay), the Munsee dialect in the north (the Hudson Valley, New York, and northern New Jersey. Their presence lived on in the names they gave to the land, the rivers and creeks, the marshes and swamps that identified this land. In the southern regions, the connection they made between the land and water is evidenced in the many place names that still identify this region known today as the “Delaware Valley.”Water is the elixir of life. It is easy to see why civilizations have developed and thrived along the rivers of the world and near the seas and oceans; for without water there is no life, and no civilization. So it was here, in the land that would become known as “Penn’s Woods,” that the convergence of two rivers, the Delaware, and it’s largest tributary, the Schuylkill, would define the land providing game, irrigation, and transportation that first supported the Lenni Lenape Nation, and then became the keystone in the building of another nation that would overshadow them.But not even the Dutch (Schuylkill) or English (Delaware) or Latinized (Pennsylvania) place names imposed by the Europeans completely obliterated the original monikers bestowed on rivers and streams and settlements by the Lenni Lenape. While Ganshohawanee, one of their names for the Schuylkill River that means “rushing and roaring waters,” its other name, Manaiunk, “the place where we go to drink,” still survives as the name of one of the neighborhoods that is nestled on the banks of this river. Ironically it is the name of the Manayunk Art Center, the physical home of the Schuylkill Valley Journal. Any school child or adult who has ever tried to correctly spell “Schuylkill” without the assistance of the Internet or a brochure, might welcome a renaming of the scenic waterway.Many of the tributaries of the Schuylkill, however, retained the Lenni Lenape heritage in their names: Tulpehocken (turtle land) Creek joins the Schuylkill west of Reading, Wissahickon (catfish stream) Creek joins the river in Chestnut Hill/Mount Airy, Manatawny (where we drank liquor; even today a winery is located nearby that bears the name) Creek joins the Schuylkill at Pottstown, and the Perkiomen (where there are cranberries) Creek joins the river near Audubon. Other tributaries, Little SchuylkillRiver, Maiden and French Creeks, have not retained their original names, although the Lenni lenape name for French Creek was probably “Winingus,” their word for mink, the animal living along its banks when the Indians first lived there (For a fascinating history of this area read “The Course of French Creek’s History” by Jonathan E. Helmreich, Professor of History from Allegheny College, which includes a discussion of the origin of the English word “buffalo,” a corruption of the French phrase “boeuf a l’eau” (water cattle).The river that most defines the region and sets many of its geographic boundaries, the Delaware, was simply called the Lenapewihittuk, the River of the Lenape, by the Nation. In a strange, odd twist, after the white settlers renamed the river, the river’s new name became the name by which the white man identified the Lenni Lenape.But a host of other names bear witness (if the reader will excuse the pun) to the Lenni Lenape connection to the land, the waterways, and the numerous animals (now equally scattered and gone) that kept them alive and thriving. The names are familiar to all of us who live in the area. They carry the sound and the soul of the “original people” who lived here, and even identify and describe a teeming landscape that has disappeared along with many of the “elders.” Places like: Aramingo, which means wolf walk; Conshohocken, pleasant valley; Lackawanna, forks of a stream; Macungie, feeding place of bears; Mauch Chunk, bear mountain (the town that is now called Jim Thorpe after the famous Olympian who lived there, whose paternal and maternal grandparents were Mesquakie/Asakiwaki and Potawatoni Indians not Lenni Lenape, tribes that were also Algonquin-language groups); Moselem, trout stream; Pocono, a stream between two mountains; and Skippack, wet land; to name a few (see A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania by Dr. George P. Donehoo).And there is the unique waterway, Neshaminy Creek, so named because of its two (nesha or nisa) bends where the Lenni Lenape trapped fish. The Neshaminy is a tidal estuary that sits at sea level and so the creek rises and falls with the tides of the Atlantic Ocean over one hundred miles to the east. The Lenni Lenape used this natural phenomenon by placing low wooden gates in the creek. At high tide, fish would swim over the gate and when the tide went back out would be trapped behind in the shallow waters, making it easier to spear them.As a boy growing up in Mount Airy, the Wissahickon was an exotic destination. It was almost a right of passage to go there, a sign that you were growing up when you were old enough that your parents would allow you to walk there and play in the woods. We were ten or twelve when we first went there, walking from out of our neighborhoods on either side of Germantown Avenue, with a packed lunch (for we would be gone all day), down the hill on Cresheim Road to the dead-end at Cresheim Valley Drive; looked both ways, and crossed the drive into “the Wissy.” It was a year ‘round trip; frozen winters saw us ice skating on the lowest of “Three Ponds” about a two-mile walk in from the drive. In summer, the more adventurous would swim in “Devil’s Pool” further along. I remember distinctly feeling the “spirit of the place” as I padded along the trails with my friends, a feeling that has never left me. Little did I know then that the spirit of the Lenni Lenape, the original people, dwelled in the creeks and streams and rivers and woods where they once lived, and where their spirit remains in the names they left behind. It was this spirit that I felt as a young boy, it is this spirit that has stayed with me throughout my life and that I hope will remain with me forever.I want to thank Chief Robert Red Hawk Ruth for sharing his knowledge with me that helped me to accurately write and correctly research this article.I would encourage readers to visit the local Lenni Lenape web site, The Root, at http://www.lenapenation.org/. And I would encourage all to visit the exhibition of Lenni Lenape culture and heritage at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology located at 3260 South Street in Philadelphia, PA 19104.Waneshi (Lenni Lenape farewell)

Copyright © 2010, Fran Baird

Essay for Schuylkill Valley Journal, Volume 30, Spring 2010Fran Baird’s poem “Neshaminy” was first published in the Spring 2009 Edition of SVJ and later appeared in the June 2009 issue of the Lenape Nation Newsletter. “Neshaminy” was nominated for a 2009 Pushcart Prize.

Events

| Unfinished Business: A Festival of Performance Works in Progress | Flying Horse Center | 6/15/2025 | |

| Save Ukraine Poetry Reading | Moonstone Arts Center | 4/3/2022 | Click here to watch |

| Poetry from Prison: Reading and Interview with F. X. Baird | Moonstone Arts Center @ PhillyCAM | 9/7/2021 | Click here to watch |

| Virtual Poetry Reading | Moonstone Arts Center | 1/27/2021 | Click here to watch |

| Virtual Poetry Reading | Moonstone Arts Center | 1/20/2021 | Click here to watch |

| Monday Poets | Fran Baird & Nausheen Eusuf | Parkway Central Library, Skyline Room, 4th Floor | 3/4/2019 |

About F. X. Baird

F. X. (Fran) Baird is the author of two chapbooks, Painting With My Father (Finishing Line Press, 2019) and Square Peg, Round Hole (Moonstone Publishing, 2021). Twin is his first completed novel.A Pushcart Prize nominee, he received honorable mention in Philadelphia Stories 2019 Sandy Crimmins National Poetry Prize. Baird studied with the poet David Ignatow at the 92nd Street Y in New York City in the early 1980’s, later with poets Cathy Smith Bowers, John Drury, and Jamey Dunham at the Antioch Writers’ Workshop, and since 2015 has studied with poet and mentor, Leonard Gontarek, as a member of the Osage Poets workshops.Dr. Baird is a retired psychotherapist, family therapist, and addiction counselor. He served in the United States Army from 1970 to 1972 following the 1968 lottery draft and was a member of both the Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Task Forces for Domestic Violence. As an adjunct professor, he taught graduate and undergraduate courses in Social Work, Psychology, Criminal Justice, and Group Dynamics at LaSalle, West Chester, and Temple Universities and was a grant writer and consultant for social service and arts organizations towards the end of his career.“Music was always a big part of my life. My mother loved classical music and opera, my father loved jazz, especially New Orleans jazz, with his favorite performer being Fats Waller. As the youngest in a large family, I grew up listening to their records and the music of all my older brothers and sisters that spanned the decades from the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s. I took piano lessons as a kid and now play the tenor sax, flute, and vibes. The influence of music, its rhythm, cadence, and sound, is evident in all of my writing. To me, language is music.”Fran was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the youngest of 12 children. He currently lives in Fort Washington, PA, with his wife, Bernadette. They have three adult children.

The Phoenix Poetry Workshop

In 2017, Fran began a poetry workshop at the State Correctional Institution at Graterford, Pennsylvania (now Phoenix Prison) which he conducts via email since the pandemic. The workshop now includes women and men from other state institutions. Poetry of workshop participants has been published in the Schuylkill Valley Journal (Fall, 2017 V45) and at Drexel University’s Paper Dragon e-zine in 2021.